Rutger Bregman's Latest Book, Moral Ambition, Is a Confusing Sequel to Humankind

Hope for homo puppy gives way to the big dog: homo startupicus

§1. This week I read Rutger Bregman’s Moral Ambition: Stop Wasting Your Talent and Start Making a Difference as soon as it came out. I tend to see myself as pretty morally ambitious and so it felt like a good fit. I admired Bregman’s previous book, Humankind: A Hopeful History (2019), ever since I read it during COVID in June of 2020. I have read it four or five times more since then. I like it so much that I have featured it in my Intro to Political Theory course at Howard University for the past six semesters. My students really love it, routinely refer to it as “life-changing,” and recommend it to their friends and family. It’s great for starting conversations about political theory because it begins where I believe all political theorizing should begin, with the study of human nature, particularly with the question of our capacity to get along with one another (or not) in the vast array of situations and communities we find ourselves in.

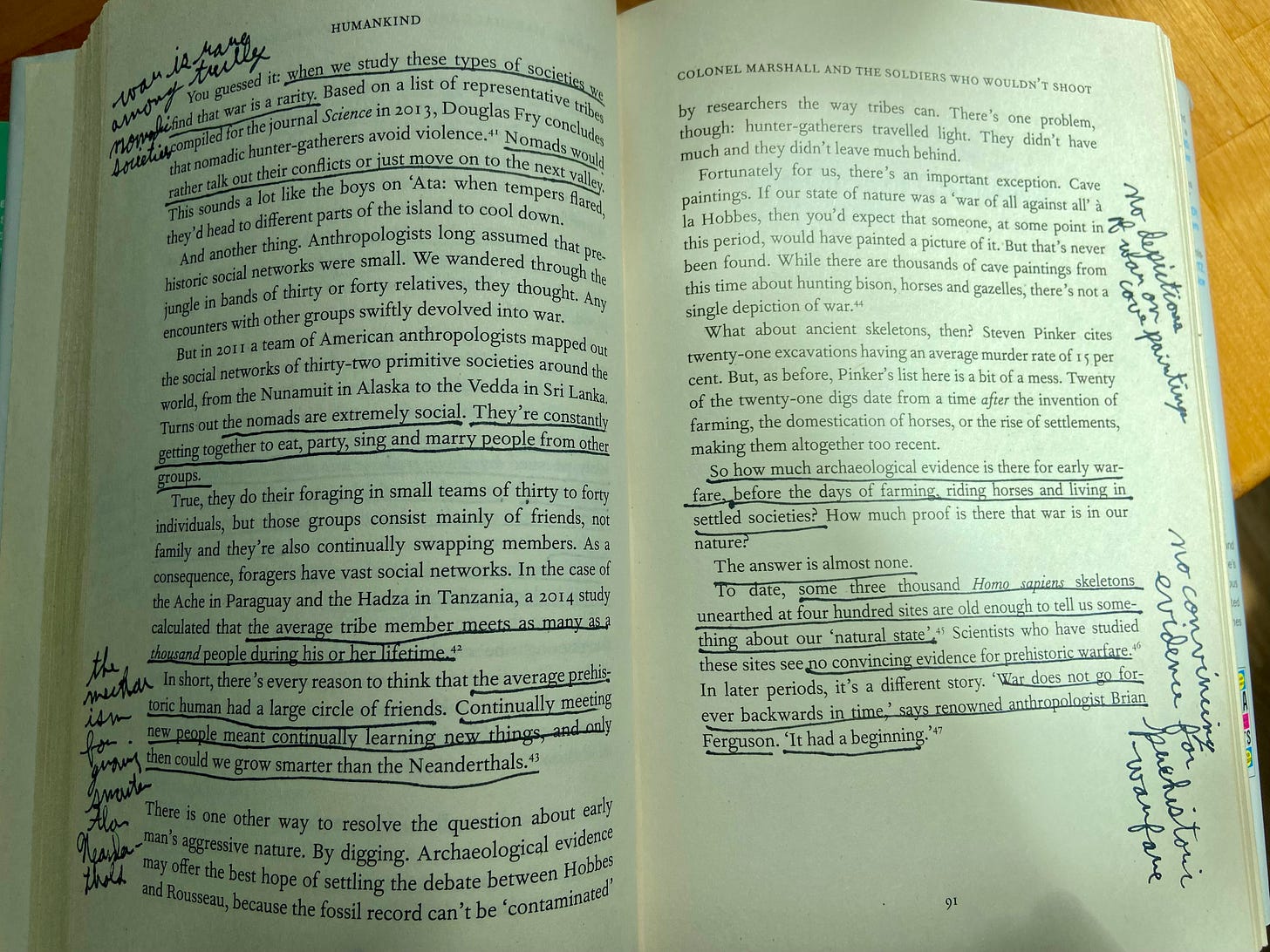

§2. Humankind is hopeful because it is a thorough, multi-disciplinary defense of the idea that “most people, deep down, are pretty decent” (2). By “decent” Bregman does not mean “angelic” or “heroic”; he means “friendly,” “prosocial,” and “loyal,” and “inclined to share and help out,” even in situations where we might not expect them to, such as in times of crisis or being on opposite sides of a war. One of the great revelations for me was that there is no evidence for prehistoric warfare. Accordingly, Bregman playfully reclassifies the human species as “homo puppy” to highlight our playful and social nature, in contrast to “homo sapiens” and “homo economicus,” which emphasize human intelligence and self-interest as the keys to our survival.

§3. What is also hopeful about Humankind is that the path forward seems clear, if arduous: human beings need to trust in their homo puppy nature (what Bregman calls “a new realism”); they need to stop ceding power to psychopathic leaders; and they need to avoid what he calls “nocebo stories,” that is, stories propagated by the media, politicians, and cynical artists like William Golding (Lord of the Flies) that, while untrue, nevertheless cause us all to behave less charitably toward one another. Bregman provides inspiring examples of businesses, schools, prisons, and governments that have operated implicitly or explicitly on the principle that most humans are decent and highlights them as the way forward. The tone of the work is unapologetically optimistic and radical.

§4. Bregman’s outlook in Humankind and the volumes of research he marshals for his thesis—including history, anthropology, primatology, psychology, sociology, neuroscience, and neurochemistry (especially oxytocin)—form some of the scientific foundation for Rise of the Benevolent Octopus, in which I offer a metaphor for leadership that, unlike most metaphors, is accessible to everyone. Not everyone can be a “lion” or a “shepherd” because these are inherently monarchical (rule of one) metaphors. But everyone may take turns leading as a benevolent octopus.

§5. I feature Bregman as a combative interlocutor with Elon Musk and have him emphasize the power of social intelligence over genius:1

Genius is a myth. Or, more precisely, human beings don’t get by on genius. They get by on being copy-cats, sharing information with one another and making incremental improvements to what came before. Humanity does not need your so-called superior intelligence, or childish obsession, to solve climate change or colonize Mars. What we need is the same access to education and to the privileged information you get by surrounding yourself with experts. The very power you arrogate to address the needs and activate the potential of others causes you to dehumanize them. You underestimate their emotional complexity and their ability to dream big and make plans of their own. You think power should position you to lead people, but it instead increases the chances that you will deactivate their potential, by ignoring or insulting them (Quasi-Rutger Bregman, RoBO 113-114).

§6. When I wrote this passage, I believed this was a pretty faithful representation of Bregman’s view of humanity, that our future lies translating our nature as egalitarian hunter-gatherers into contemporary settings. Which is why it is hard for me to reconcile the kind of human that Bregman sees as our hope in Moral Ambition. His opening chapter, “No, you’re not fine just the way you are,” seems like an implicit, but harsh repudiation of homo puppy (unless I missed it, this crucial term from Humankind is nowhere to be found in Moral Ambition).

§7. Consider Bregman’s description of moral ambition:

Moral ambition is the will to make the world a wildly better place. To devote your working life to the great challenges of our time, whether that’s climate change or corruption, gross inequality or the next pandemic. It’s the longing to make a difference—and to build a legacy that truly matters (3).

Bregman does not locate the term “moral ambition” in any historical or cultural context. For the most part he acts as if he has just made a novel observation about human behavior. I continually wondered how moral ambition differs from courage of conviction (see Ida B. Wells’ “Requisites of True Leadership”)? From reincarnated Stoicism? From leadership? Or morality itself? I thought that maybe you needed the word “ambition” since people do so much living online these days that the distinction between online morality and real-world morality matters.

§8. Bregman’s description of moral ambition reminds me a lot Aristotle’s great-souled man (megalopsychos) in the Nicomachean Ethics, or of the high-mindedness (megalophrosune) of Pericles or Alexander the Great in Plutarch’s Lives, or even of the modern Greek concept of philotimo. The only related concept that Bregman contrasts moral ambition with is the concept of “effective altruism” popular among tech billionaires. For Bregman effective altruism is somehow more robotic, more prone to corruption (see Sam Bankman-Fried), and more complacent about the status quo (157-162). Apparently, “ambitious altruism” and “ambitious impact” were already taken. But I more concerned with Moral Ambition in relation to Humankind.

§9. Accordingly, I want to highlight in this article some of the confusing points of contrast I see between Bregman’s two works. I am confused most of all by the fact that Bregman does not seem to acknowledge these contrasts, much less explain how or if his thinking has evolved. In fact Humankind’s thesis, that most people, deep down, are pretty decent, is mentioned only once in passing (29). For shorthand, I will refer to the morally ambitious person as “homo startupicus” for all the emphasis Bregman places on the start up as the partnership (or koinonia, to borrow a term from Aristotle’s Politics) that is most conducive to human salvation.

First Confusion: Stories from Humankind are either repurposed or their lessons reinterpreted in Moral Ambition

§10. Mattieu Ricard, a Buddhist priest who spent more than 60,000 hours in meditation, is held up in Humankind as a model for emulation. Through meditation he used his brain for compassion (caring that other people fare better) rather than empathy (trying to imagine people’s suffering, Humankind 386-387). In Moral Ambition, however, Ricard becomes the poster child for the “Noble Loser,” a person who wasted thirty working years and “didn’t lift a finger to make the world a better place” (xii). Only at age fifty-four does Ricard redeem himself in Bregman’s eyes as homo startupicus by creating a non-profit to do humanitarian work in Tibet, Nepal, and India, while donating the proceeds of his talks and books (223-224).

§11. Indeed empathy (over compassion) is redeemed somewhat in Moral Ambition. Bregman tells the inspiring story of Rob Mather, a British consultant who went on to found a highly effective non-profit for providing malaria nets in Africa. Mather’s impetus for doing charity work was catalyzed by his acute empathy for a little girl who was severely burned in a house fire (“I was streaming,” 90). Yet in Humankind one of Bregman’s “Ten Rules to Live By” is to “Temper your empathy, train your compassion” (386), the idea being that empathy is an irrational and debilitating “searchlight” that causes us to prioritize the suffering of one individual over a larger societal problem.

§12. Also in Humankind Bregman disputes the traditional lesson of the Stanley Milgram shock experiments conducted at Yale University in 1962, namely, that human beings are inclined to blindly follow authority, to the point of astonishing cruelty. Bregman points out on the contrary that many people resisted these experiments or complied with them only because they thought they would be benefiting humanity through science. He bolsters the claim that humans are naturally prone to resistance with a story of how the Danes warned Danish Jews of an impending Nazi raid during WWII. For Bregman the impulse to resist was spontaneous and thus indicative of humanity’s inherent decency:

When news of the raid spread, resistance sprang up from every quarter. From churches, universities and the business community, from the royal family, the Lawyers Council and the Danish Women’s National Council—all voiced their objection. Almost immediately, a network of escape routes was organised, even with no centralized planning and no attempt to coordinate the hundreds of individual efforts. There simply wasn’t time. Thousands of Danes, rich and poor, young and old, understood that now was the time to act, and that to look away would be a betrayal of their country (my italics 177).

§13. But in Moral Ambition saving Jews turns out to be not the spontaneous work of a decent mass of Dutch people in the town of Nieuwlande (many of whom thought resistance was futile) but of a few relentless advocates, the leader of whom, Arnold Douwes, believed most people were cowards (29). Douwes himself does not easily fit the profile of a “decent” person. Bregman describes him as a willful child, suspended from school, unable to find a job or a wife, a “freewheeler” and a “drifter.” Nevertheless, Douwes took lots of initiative to resist the Nazis and created one of the largest networks for hiding the Jews. According to Bregman he did not convince people to house the Jews in their homes by appealing to their better natures, but by shaming them, for example, calling ministers cowards and faithless. Nothing in Douwes’ profile speaks of decency other than the results: he saved tons of lives. Several of the people that Bregman celebrates as morally ambitious behaved questionably on an interpersonal level in order to make the world “wildly better.”

Second Confusion: Homo Startupicus is all work and no play

§14. Chapter 14 of Humankind is called “Homo Ludens” (“playing man”), and it is paired with the previous chapter on the power of intrinsic motivation. Taking his cue from the work of the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga, who said that play is the foundation of all culture, Bregman celebrates humans at play and laments the mental health consequences of our loss of playtime. He features the junkyard playgrounds of Carl Sorensen and the Agora school of Sjef Drummen, where kids make up their own curricula and pursue their interests as they arise. Bregman “sees every reason” to believe that this school would work for most children (293).

§15. By contrast, the paradigmatic school in Moral Ambition, dubbed the “Hogwarts for do-gooders” (as if the original Hogwarts did not set out to do enough good), is Charity Entrepreneurship. The “school” is highly competitive, having turned away Harvard Ph.D.’s, and is committed to helping students start their own non-profit as quickly as possible to do the most immediate good possible, especially in developing countries. Bregman quotes the director of the school, Joey Savoie, on the importance of hard work: “You can set your own hours. As long as it’s all of them” (107).

§16. Indeed most if not all of the morally ambitious people in the book work very hard for their entire lives and eschew personal relationships in service to their cause. The work’s central hero, Thomas Clarkson, whom Bregman credits with the pivotal role in ending the slave trade, had to take an eleven-year sabbatical after a nervous breakdown in his thirties (224). Bregman concedes that there is more to life than moral ambition, but then says, “Most people still have a long way to go and haven’t come close to reaching the bounds of their moral ambition” (224). It doesn’t seem to me that Bregman has found a way to balance the change he wants to see in the world with what he had already celebrated as a central feature of our humanity, namely, our love of play. The book concludes with the announcement of Bregman’s own new “School for Moral Ambition,” but it would be wise to keep in mind that the origin of the word “school” is the ancient Greek “skolē” or “leisure.”

Third Confusion: Trickle-down shamonomics

§17. In Humankind shame is hailed as a time-honored means by which powerful braggarts are brought down and reintegrated into society—or banished from it altogether. If a hunter claims his meat is the best or a politician claims that he was sent from god, the remedy is the same: mock them until they blush. If they cannot be made to blush, get rid of them. Our human ancestors according to Bregman were “allergic to inequality” (95).

§18. By contrast, the morally ambitious person rises above the common herd:

[M]ost humans are herd animals. We do what we’re taught to do, we accept what we’re handed, we believe what we’re told is true. Though we may feel free, we’re sticking to the script that goes with our kind of life (Moral Ambition 25).

§19. Bregman cites the Pareto Principle that most of whatever gets done is accomplished by 20% of the population, while the other 80% just goes with the flow. For him the same is true of positive influence, which he sees as a hopeful prospect. If you do happen to be morally ambitious, you can expect your actions to go a long way: “the best charities are fifty times (!) more effective than the median charity and a whopping 10,000 times more effective than the worst ones” (155).

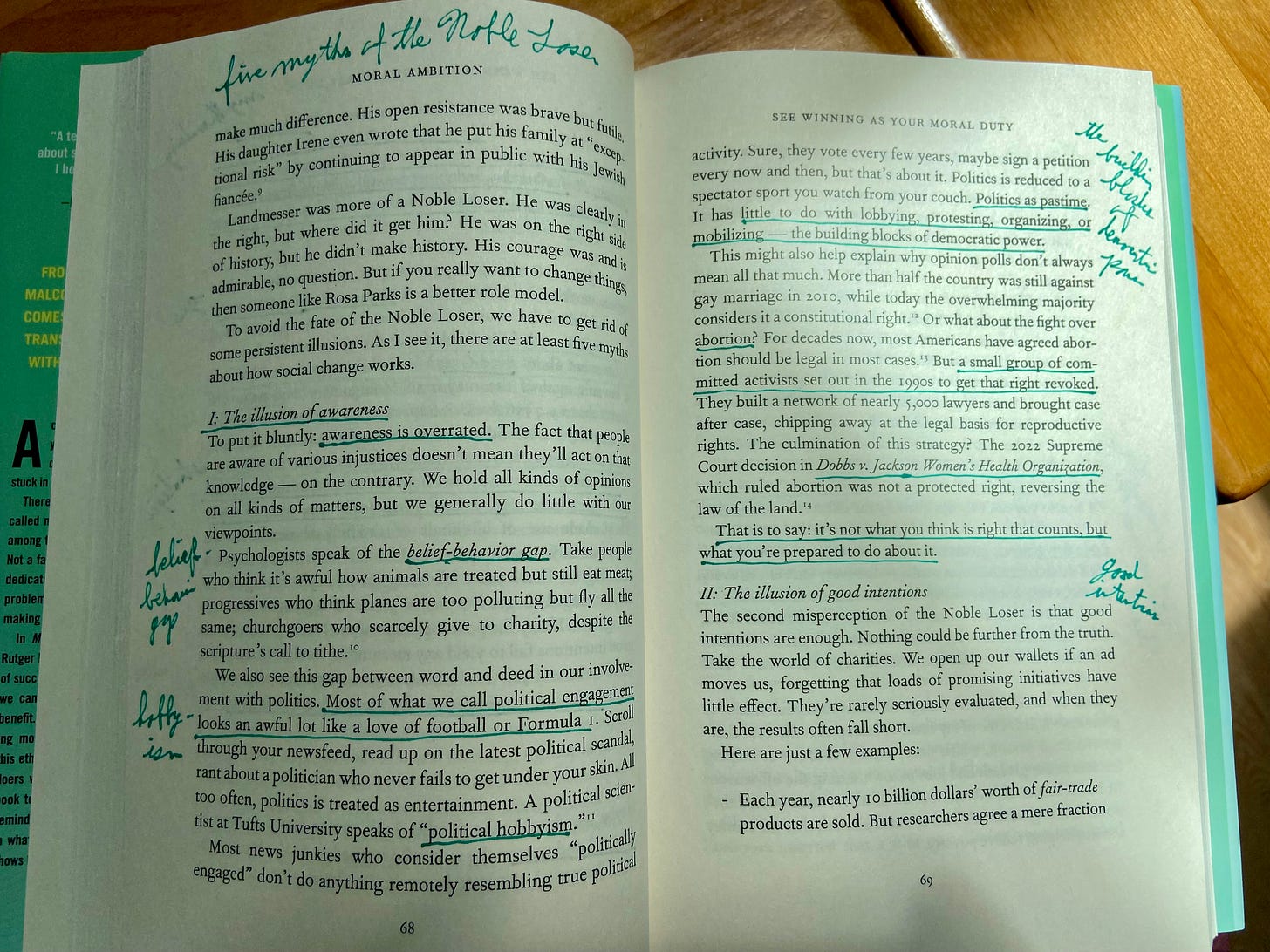

§20. And rather than the shame working from the bottom up, in the world of homo startupicus, the shame trickles down. All the people who are not doing enough, need to be told what’s up. Bregman insists that he doesn’t mean to shame or guilt people into being ambitious (“we’re not driven by feelings of guilt, but by sheer enthusiasm” 231), but this claim is not supported by his tone or language throughout the book. Those who fail at being morally ambitious are deemed “Noble Losers” (on which see pp. 68-80). “Loser” can just mean, “someone who lost,” but in the context of moral conversations, it seems much likelier to mean someone who lacks character and initiative. If Bregman intends to shame others, I feel like he should just own it.

Fourth Confusion: Humankind embraces complexity, Moral Ambition minimizes it

§21. Humankind charts Bregman’s own intellectual journey toward his conclusion about human decency. He tells you the questions he’s grappling with and how he tries to answer them. He acknowledges his previous misperceptions (e.g., being persuaded that humans without civilization are savage by Steven Pinker’s Better Angels of Our Nature, 78), and he revises his claims (see his chapter on the tension between the will to doubt of Betrand Russell and the will to believe of William James, 253-262). His account of human nature seems balanced across so many different disciplines and human institutions.

§22. Moral Ambition, by contrast, is a presentation of foregone conclusions. We get very little sense that we are on an intellectual journey. Rather, the narrator is much more morally certain of himself, yet the narrative feels unbalanced. Bregman spends many pages on solving the problem of animal cruelty and ending diseases. He identifies three existential threats to humanity: nuclear war, artificial intelligence, and engineered pathogens. Yet less than a page is devoted to gaming out the problems of artificial intelligence or teasing out how a morally ambitious person could do anything to address them (201). While saving democracy was central to humanity’s future in Humankind, there is virtually no mention of the rise—and persistence—of authoritarianism in Moral Ambition and no formulas for or examples of someone who took down a tyrant. The deleterious effects of social media to human communities and relationships, so well documented by Jonathan Haidt, are also not mentioned.

Fifth Confusion: Bregman seems to have made peace with Steven Pinker

§23. In Humankind Bregman calls Steven Pinker’s best-selling book, The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011), “ a massive doorstop of a book” (78), and Pinker himself is “the psychologist of the weighty tome” (85). Bregman argues that many of the statistics that Pinker uses on the violence of earlier cultures are “mixed up” (88-89). He is not as harsh toward Pinker as others in the book, but he seems to see him as a type of morally-questionable public intellectual who perpetuates toxic nocebo stories (see Bregman on Philip Zimbardo, Stanley Milgram, and Jared Diamond).

§24. In Moral Ambition Pinker is now the voice of optimism behind the morally ambitious spirit:

Of course, we’re now well aware of the huge downside to our unchecked fossil fuel use. But let’s say we succeed in making our energy supply green and clean. And say we then have at our disposal 700 times as much energy per person.

Then the wildest fantasies can become everyday realities.

“The team that brings clean and abundant energy to the world,” writes psychologist Steven Pinker [no longer “of the weighty tome”], “will benefit humanity more than all of history’s saints, heroes, prophets, martyrs, and laureates combined” (Moral Ambition 135).

I could write for days on the dubiousness of Pinker’s claim, starting with the story of Aladdin and the Lamp.

§25. For his part Pinker praises Moral Ambition, calling it “A new look at how to make the world a better place, guided by reason, balance and engaging case studies. Bregman avoids easy moralising and lazy conventional wisdom to offer a fresh and practical guide to idealism” (see the front matter).

§26. Side Note: Peter Thiel is regarded in Moral Ambition as perhaps “one of the most dangerous men in America,” but also to be appreciated for his cult-like approach to getting things done (47-48, 52).

Sixth Confusion: Contrasting faith in humanity and civilization

§27. Humankind is agnostic about civilization itself. Bregman spends an entire chapter enumerating the ills that befell humans once they decided to live in fixed settlements and own property, including xenophobia, war, the STD’s, religions with vengeful dieties, and the patriarchy (94-112). To the question “is civilization a good idea?” Bregman replies curtly, “Too soon to say” (112).

§28. But Bregman is hopeful in Humankind that human decency can overcome even existential threats like climate change. After he makes his case that the tragedy of Easter Island was not the result of reckless deforestation and savage civil strife on the part of the natives, he insists that the fate of the world is not as bad as people think it is:

I’m no sceptic when it comes to climate change. There’s no doubt in my mind that this is the greatest challenge of our time—and that time is running out. What I am sceptical about, however, is the fatalistic rhetoric of collapse. Of the notion that humans are inherently selfish, or worse, a plague upon the earth. I’m sceptical when this notion is peddled as ‘realistic’, and I’m sceptical when we’re told there’s no way out.

Too many environmental activists underestimated the resilience of humankind (my italics 134).

§29. Again, Bregman is making the case that human decency gives us a resilience that can solve major problems. Humans fail, Bregman argues, when some powerful overlord takes them over and subjects them to slavery or pits them against one another.

§30. Moreover, in Humankind the so-called Dark Ages are to be admired, as a period of reprieve from the ills of so-called high civilization, “when the enslaved regained their freedom, infectious disease diminished, diet improved and culture flourished (109). In Moral Ambition Bregman worries that future generations will look down on us as people of the Dark Ages for not working hard enough or intelligently enough to solve our problems (136).

§31. Bregman is still able to pro and con human civilization in Moral Ambition, but not to the radical degree he went to in Humankind. Here he is much more alarmist (“Our power has become so great, so all-encompassing, that it’s threatening our own existence—and that of all future generations, 199), but also a techno-optimist. Indeed, moral ambition seems to align well with techno-optimism, as Bregman looks forward not to “saints, heroes, prophets, martyrs, and laureates,” but to homo startupicus.

Seventh Confusion: The contrast between a human trait and a mindset

§32. Humankind is all about human nature. For Bregman our decency is rooted in our DNA and in our evolution. Our faces, as Bregman says, “leak emotions” (69). We are social and communicative in our very anatomy, being the only creatures with whites in our eyes and the capacity to blush. We’re one of the few creatures to express emotions with our eyebrows (dogs are another great example). Once you realize this about our anatomy, you can’t stop noticing how many cartoon animals and robots get these features in story-telling as a way of humanizing them.

§33. Bregman believes that homo puppy can, under the right circumstances, form mutually beneficial communities and marshal our collective intelligence and energy. One heartwarming example in Humankind is that of participatory budgeting, a radically democratic feature of some governments, whereby all citizens are given the chance to articulate the needs of the community and allocate the necessary funds. These contributions transcend expertise. Bregman asserts, “Time and again, researchers remark on the fact that almost everybody has something worthwhile to contribute—regardless of formal education—as long as everyone’s taken seriously” (304). Bregman is derisive of anything less than this full participation:

Political debates can be so complex that people have a hard time following along. And in a diploma democracy, those with little money or education tend to be sidelined. Many citizens of democracies are, at best, permitted to choose their own aristocracy.

But in the hundreds of participatory budgeting experiments, it’s precisely the traditionally disenfranchised groups that are well represented. Since its 2011 start in New York City, the meetings have attracted chiefly Latinos and African Americans. And in Porto Alegre, 30 percent of participants come from the poorest 20 per cent of the population.

‘The first time I participated I was unsure,’ admitted one Porto Alegre participant, ‘because there were persons there with college degrees, and we don’t have degrees…But with time, we started to learn.’ Unlike the old political system, the new democracy is not reserved for well-off white men. Instead, minorities and poorer and less-educated segments of society are far better represented (303).

§34. Moral Ambition seems all about human nature, too, but exceptional human nature—and privilege. The subtitle of the book, Stop Wasting Your Talent and Start Making a Difference, concedes this (for not everyone has “talent”), and the majority of the examples featured in the book are of highly-educated high-achievers. They have a personality characterized by self-confidence, disagreeableness, and “cultlike” devotion to a cause (33-35). For Bregman it is now better to belong to a cult than a herd.

§35. Bregman tries to downplay moral ambition’s implicit elitism by characterizing it as a “mindset,” and he likens it to an infection that someone may just “catch” (“Moral ambition isn’t a trait; it’s a mindset,” 225). I am at pains to understand this distinction between a trait and a mindset, given the profiles of all the morally ambitious people in the book. While it may be true that anyone deciding to do massive good in the world at any moment makes their decision on the basis of all sorts of random factors (a TV show, inspiration from a friend, boredom at work), their execution of that decision seems to depend largely on some prior set of traits beyond decency. And the resources they call upon—wealth, social networks, geographical location, and education—are well beyond those of the average person. You can be poor and decent, but it’s hard to be poor and morally ambitious.

§36. For me Bregman has lost the distinction of being a radical thinker, though I am grateful for his enthusiasm, and all of the stories he shares are pretty hopeful and inspiring (though note how much he wants you to become like Ralph Nader’s Raiders rather than Nader himself). The vision of the world offered in Moral Ambition is not that different from an Aspen for young people or what tons of colleges and universities are doing across the globe with various social entrepreneurship programs. It may be that the version of moral ambition that Bregman’s school promotes will be more successful than what others have tried, but I see no reason to believe so. My worry is that Bregman’s school and others like it will contribute to the trend of performative education, whereby we highlight a few success stories of a few different programs rather than acknowledge the deep, but fixable, problems in more established systems like higher education. For example, lack of student commitment to saving the world in wildly audacious ways has much more to do with their experience of higher ed than it does with any lack of moral ambition. In order to get any kind of advanced education many students must get tens of thousands of dollars into debt. It is no wonder that many take meaningless jobs in order to pay off that debt. If we want to increase the chances that young people will save the world, we need to invest in all of them, not just the select few. Programs that favor the select few, however inspiring, seem like a distraction. That is why I will continue to put my hope in the human decency celebrated by Humankind more than the extraordinary genius, self-confidence, social distance, and hard work offered by Moral Ambition. I would love to read a book where Bregman tries to reconcile the two into something like Plato’s kallipolis.

Appreciation for Moral Ambition

§37. I want to conclude with something I am enthusiastically grateful to Bregman for in Moral Ambition: his eloquent sympathy for animals being raised and slaughtered in meat factories. We are fortunate to live in an age of increased awareness of so many forms of human suffering. Yet we spend many hours discussing this suffering over the dinner table, fed by animals whose suffering we don’t even comment on. I have long wondered why this is, but I am super-grateful to Bregman for calling attention to it so forcefully. My family and I have resolved to educate ourselves more and to significantly curtail our consumption of animal products. Bregman’s moral ambition has indeed infected us in a positive—and hopefully permanent—way!

See Chapter 3 of Humankind, “The Rise of Homo Puppy,” especially Section 5 (pp. 68-72), which makes the case that humanity’s “superpower” is social intelligence.

I wish I read this review before purchasing the book, will read to see what conclusion and positives I can glean from the writings.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/17/magazine/rutger-bregman-interview.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare