‘Arma virumque cano!!!’ No introduction. No preface. He sounds like an irate pirate the way he trills the ‘arrr’ in ‘arma.’ But he never stops smiling. He was fresh from a sabbatical year at Oxford and one year away from winning the most prestigious teaching prize in classics from the American Philological Association. Which is to say he was at the top of his game, and ebullient.—Rise of the Benevolent Octopus 220

§1. I have been on Substack now for only two months, so I don’t know whether it is because of an algorithm or an increased interest in the Substack community, but I am seeing an uptick in posts about the decline of higher education, particularly about the supposed decline in the quality of our students. The features of this decline are familiar to anyone reading this post: students can’t read, can’t write, can’t concentrate, aren’t curious, and cheat all the time to give the impression that they are. The alleged reasons for this decline are also familiar: the preprofessionalization of higher ed that cares very little for reading, writing, and thinking;1 the loss of focus on character development through great, canonical (or “Western”) texts; and the black-hole voraciousness of social media.

§2. The decline is real and thus worthy of attention, and while I acknowledge that calling attention to a problem is often a form of leadership in many cultures across time, I have often wondered whether complaining about a problem to an audience that may be in no position to do anything about it counts as leadership. Accordingly, I’m not going to try to tackle this problem here in any systemic way. Instead, I want to argue that there is still something meaningful that a single professor of higher education can do while the decline persists. I simultaneously want to pay tribute to the many teachers and professors I’ve had over the years who did this one thing, especially my college Latin professor, Dr. Gerberding.

§3. In Rise of the Benevolent Octopus I present a form of leadership that is grounded in deep and diverse perspective taking, which I term “noöphilia,” or “loving the minds of others.” You can love another mind for many reasons: its patterns of thought, its way of feeling about the world, its interests and motivations. It is this last aspect that I want to focus on here. Human beings are imitative creatures and one of the things we imitate about one another are our likes and dislikes. Parents get their babies to try new food by seeming to like it themselves. People on cooking shows do the same thing. Advertisers sell products by showing someone who relishes them. Faith leaders win converts by performing their all-consuming love of the deity.

§4. Thus a leitmotif of the book is the transmission of a passion from one mind to another. I quote the instantly-inspiring conductor Angel Gil-Ordóñez who says, “you don’t learn to love a subject from the subject; you learn to love a subject from someone who loves the subject (RoBO 224). I talk about how my father hated bluegrass music as a child but somehow his father’s love for it remained in him despite the bitterness of their relationship (RoBO 181).

§5. For my entire professional teaching career I have been told by one expert or another that the key to my success as a teacher going forward is (1) to “meet my students where they are,” that is, to find out what they’re interested in and work from there and (2) to adopt the latest technology to hold their interest. This technology includes resources to capture and hold their attention in the classroom (dry erase boards, PowerPoint presentations, video, sound, graphics, and ideally a more famous guest speaker than yourself) and course management platforms to ensure that students can monitor their assignments and grades in real-time. When these two approaches don’t work, the remedy is always to anticipate even better technology down the road and to get to know our students even better.

§6. I have incorporated some of the recommended tools into my teaching from time to time, but I mostly keep them in the background. I do make an effort to understand my students because I truly find them interesting, but not to the degree that experts often advise. For example, I don’t bother to understand them in generational terms or try to wrap my mind around their individual learning needs. I tend to assume what the gruff Roy Kent in Ted Lasso tells Rebecca Welton, that kids don’t need a parade; they just want to be part of our lives (here’s the hilarious clip). I do this not because I don’t care that much about my students or technology but because—I am here to tell you—the most powerful teaching tool is not Blackboard or Canvas, it’s not more immersive or “experiential” learning, it’s not ChatGPT writing your lectures for you, it’s not cameras and audio equipment capturing those lectures so that students can watch them on their own time. Believe it or not, even your love for your students is not the most important tool (though it is important). Rather, it’s the all-consuming, boyish, girlish, silly, playful, deep, committed, and serious love for your own subject.

§7. Many readers can convince themselves of the truth of what I say by thinking of their own example of someone who introduced you to a subject you knew almost nothing about but their love convinced you to take it more seriously and in some cases you took it so seriously that you fell in love with it, too. I will share the example of my Latin professor Dr. Gerberding, and you can see what elements seem familiar to you.

Dr. Richard “Dick” Gerberding’s Love of Latin

§8. I was in the fall of my sophomore year in college at the University of Alabama in Huntsville. I was majoring in physics and minoring in math, and considering double-majoring in philosophy. I decided to take Latin because I was required to have four semesters of a foreign language and because I was interested in word origins.

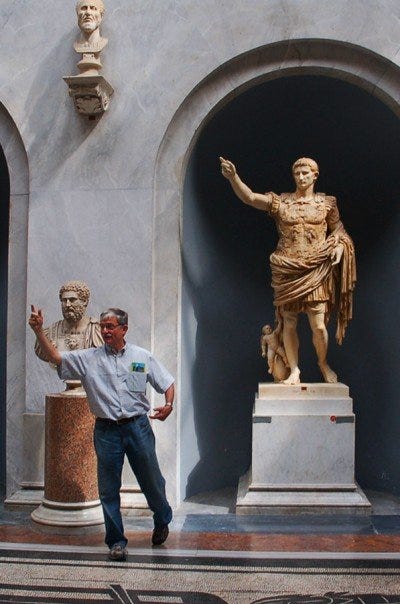

§9. As I detail in the book, this was how the course began:

‘Arma virumque cano!!!’ No introduction. No preface. He sounds like an irate pirate the way he trills the ‘arrr’ in ‘arma.’ But he never stops smiling. He was fresh from a sabbatical year at Oxford and one year away from winning the most prestigious teaching prize in classics from the American Philological Association. Which is to say he was at the top of his game, and ebullient.

§10. Dr. Gerberding would make us repeat these opening lines to Vergil’s Aeneid, the epic poem about the founding of Rome, at least two hundred times that semester. He made us memorize the first eight lines and repeat them on our exams. And the more we memorized, the deeper our analysis would go, into the meanings of the words, the grammar, the metrical rhythms, and the literary and cultural history behind the work. The meaning he could wrench from a few syllables seemed infinite. He would fill an already full conversation with asides about the Latin professors he had had and the first time he learned the real, deeper meaning of a word. He would extend our study into the future, through the rise of Christianity and the Renaissance and into the modern world, pointing out the all the residue of Latin in legal phrases and university seals. His curiosity would spread out wondrously willy-nilly like drops of ink in water, until, mirabile dictu, everything was about Latin.

§11. If he didn’t start the class by boisterously chanting the Aeneid, he would give us short Latin phrases to pick apart and ingrain into our habits, like “repetitio mater memoriae” (“repetition is the mother of memory”). He promised us facetiously that we could use these phrases “to impress our roommate” (“contubernalem movere”). Horace once said that teachers give cookies to their students to reward them for learning their lessons, but these choice phrases were the cookies.

§12. Class time itself was more of a choral practice than anything else, with Dr. Gerberding marching up and down the aisles leading us in the recitation of our paradigms and calling on us to be ever louder and clearer in our pronunciation. When he called on us, he made us read with conviction, with attention to the meaning of each word. If you got something wrong, he would often tease you for a lapse of memory or lack of preparation. For me at least that was o.k. What we were learning was so important that it was good to be kept honest about what you knew and didn’t know.

§13. Dr. Gerberding’s love of Latin was on display every day in large and small ways, but mostly for the fact that he never tired to reading the same introductory sentences from Wheelock’s Latin Grammar and contemplating them from new and different angles. His love extended into a spontaneous joy in seeing students grasp a new and difficult idea, like the perfect passive participle or the ablative absolute. He would light up when he realized that the concept was forever solidified in a new brain. But primarily his interest resided in the field itself. He used to tell me all the time about how much the study of Latin opened up his own mind, how he was now doing mental gymnastics he never thought he could do. He loved how the etymology of a word could unlock ideas he’d never considered before. He loved connecting with the tragic and brilliant poets, writers, and historical figures we were studying. It made him a better friend, a better teacher, and a better citizen. He didn’t learn about these people; he learned from them. And to no small degree he loved Latin because it was hard, because it took a ton of concentration and effort. He loved that the more effort you put in, the more you got out. When he founded the student-run Society for Ancient Languages, he gave it two mottoes, one in Greek and one in Latin:

χαλεπὰ τὰ καλά: “beautiful things are difficult” (taken from Plato’s Republic)

otium cum dignitate: “leisure with dignity” (taken from Cicero’s Pro Sestio)

A Path to Improving Higher Ed

§14. I think anyone who has in mind someone who inspired them with their love of a subject has an intuitive grasp of what good teaching looks and feels like. This understanding also makes you a pretty good critic of a lot of educational theory. For instance, consider the way many professors are dismissed as a “sage on the stage” rather than the “guide on the side” (just because it rhymes doesn’t make it true). This has always seemed to be a false choice to me. I want to see not only a sage on the stage, but real, three-dimensional human being, who’s deeply passionate about whatever sagery they’re practicing. I don’t just want information; I want to know what it’s like to live the life of someone who studies this subject. Good professors are so much more than “content deliverers” and “facilitators.”

§15. And it’s o.k. for someone who loves their subject to give a lecture about it. Trust me, students will pay attention. The fact that there are so many examples of people just talking online—podcasts, stand-up comedy, news interviews—proves a fortiori that people have the appetite for watching someone talk in person.

§16. You may be wondering if Dr. Gerberding was able to share his love of Latin because he had a lot of community and administrative support. On the contrary, his love of Latin was barely supported at all. Every semester he taught Latin, he taught it as an overload. He rarely got to teach a class beyond the fourth semester. He had to find people in the community to teach the Latin classes he couldn’t teach because the university wouldn’t hire someone permanently. Faculty in his own history department looked down on his teaching as not current or trendy enough to meet the interests of its students. UAH being a STEM school, many students who signed up for his classes did so because they had to, not because they cared anything about Latin (this was before apparently all males fantasized about Rome). In fact the engineering department told its students not to take his classes because they were too time consuming and would ruin their GPA. Some students who were interested to take Latin because they thought it would teach them more about Christianity were quickly put off by all the memorization they were required to do. Whenever he couldn’t find the funds from the university to cover a student trip to the Nashville Parthenon or buy tickets to a local play, Dr. Gerberding would secretly pay these expenses himself. He suffered a lot of indignity to promise leisure with dignity.

§17. You may also be wondering if Dr. Gerberding was some kind of a sap for caring so much in spite of all these indignities. Again, on the contrary, his brazen love for Latin made him hilariously irreverent. He had found the key to leisure with dignity and could mock and pity those who hadn’t. Sometimes on a Latin quiz he might gloss barbarus, -i, n. as “university administrator.”

experiencing someone’s love of a subject is the most important form of experiential learning a student can have

§18. For my part I think it makes it easier to bear the problems in higher education by being open about my passion for learning. It’s not important for all students to love the subject as much as you do or even in the same way as you do. Some will love it for similar reasons as you, and some may hold on long enough to find their own reasons, just because they see how much you care about it. But even if most students just don’t care, the odds can be pretty good that they may find at least one subject in college to really love, assuming their other professors take the time to profess their love. And that’s a pretty hopeful scenario.

§19. Because professors are in fierce competition with so many other people voicing their love of things other than learning—money, power, food, fame, ease, comfort—we must respect that experiencing someone’s love of a subject is the most important form of experiential learning a student can have. Accordingly, we must use whatever means we can to share our love of learning.

Tips for Showing Your Love

§20. Here are my best tips, but I welcome comments from teachers on how you share your passion for your subject:

Channel the lovers of learning who came before you. Reflect on them until it makes you smile.

Remember why a subject, a work, or a topic once mattered to you when you were the students’ age. Explain how its relevance may have changed over time.

Tell stories about the history of your relationship with the subject, how it got started and how it evolved. Tell students how it changed your life. Doing so will give you a better sense for how they might connect with it.

Tell students why a subject matters to you right now. Tell them how studying it can improve their lives and those around them.

Tell students why a subject has mattered to other people.

Let students share why a subject does or does not resonate with them. Tell them it’s o.k. not to like it but they have to try it; the trick is to not like it for sophisticated reasons. They can often learn a lot about other people and themselves when they try to do this.

Don’t teach material you don’t love. I realize some faculty are constrained by departmental programs to teach certain courses, but in my experience there is usually enough flexibility to teach different works within a course. And even when the same works are required of everyone, there are opportunities to highlight your favorite passages and explain to your students why those matter most. For instance, I have taught Intro to Political Theory about ten times in the past three years and I still find new and fascinating things to explore with my students. After all, the world is living through political theory right now.

Be honest with yourself about your love. Ask yourself if you still love the things you teach for their own sake. Ask yourself if you would study them even if you weren’t paid or recognized for doing it. If you don’t love your subject anymore, try to rekindle it or find a subject you do love. It’s o.k. to find a new love, but you should not be surprised if your students don’t care to learn something you no longer care about. They are surrounded by videos of people who are quite adept at performing their care for other things.

Be irreverent in your love. Criticize, mock, and pity all those in power who haven’t sought or haven’t found a love for learning that runs as deep as yours.

Caveat: in encouraging professors to share their love of a subject, I’m not encouraging a professor to try to be “cool” and share every intimate detail about their lives. You probably don’t need to tell students what you have for breakfast every day or about that time you followed some girl to every Phish concert in the summer of ’99. Dr. Gerberding’s lack of coolness made him most endearing. He was all about the learning.

Legacy Books

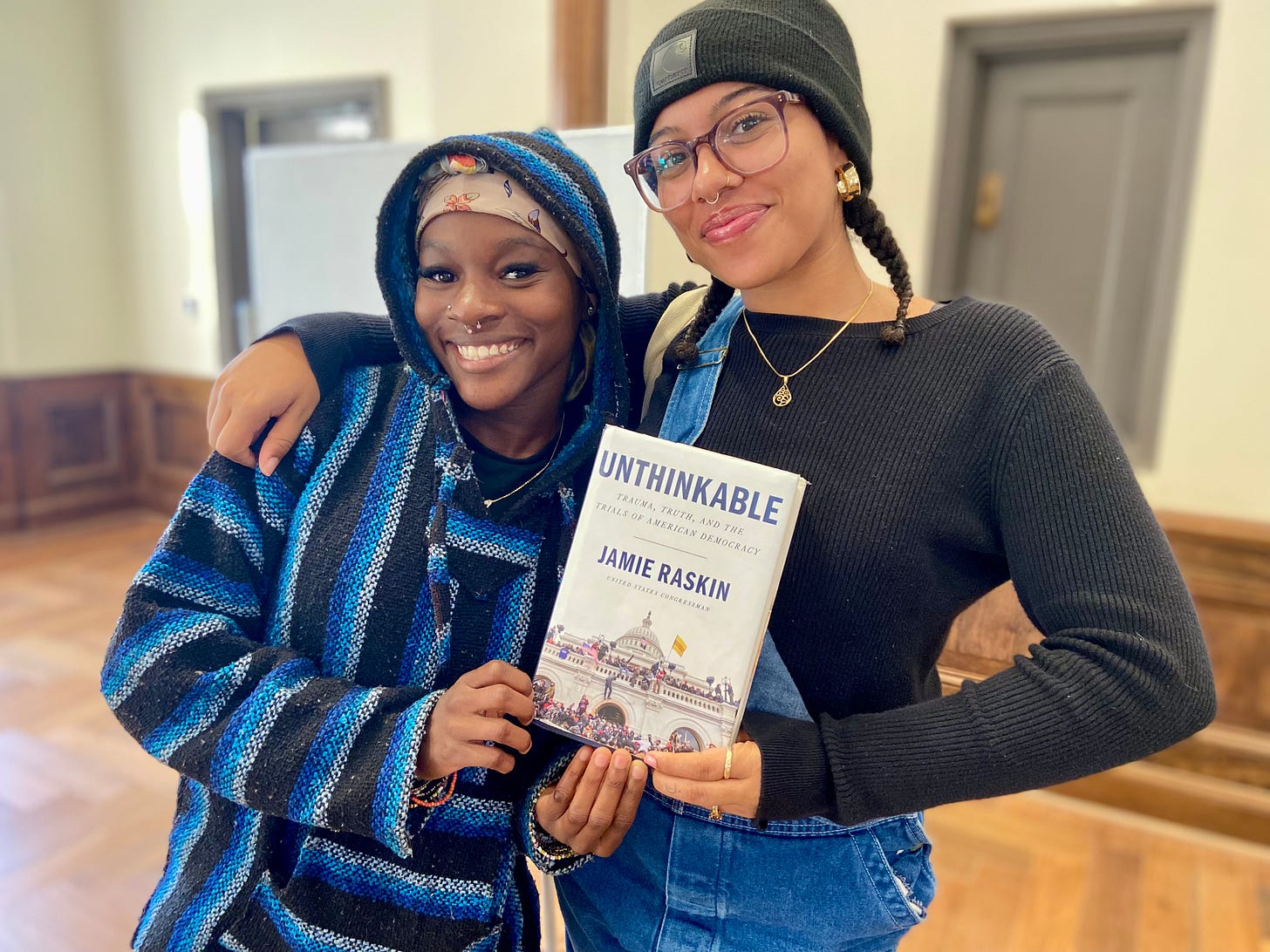

§21. Here’s one last way to connect with students over a love of learning. I like sharing personal copies of my favorite books. I give a student two weeks to read one and then I have them sign the inside front cover. Every new reader get to feel like they are part of a legacy of reading and dialogue with the book. Sometimes the conversations we have about these books are deeper than the ones we have in class because students are choosing something they want to read rather than something they’re assigned.

Coda: A tribute to many teachers who lived the principle of “teach with a love for your subject” (there are many others)

Penny Nugent, my sixth-grade elementary school teacher

Carole Merritt, my AP US history teacher

Joyce McMichael, my AP chemistry teacher

Gordon Emslie, my honors physics teacher in college

Brian Martine, my philosophy professor in college

Bill Race and George Houston, director of graduate studies and department chair when I began grad school at UNC-Chapel Hill in 1999. In our orientation they said to us, “Classics is hard, but if you ever forget why you love it, please come to us and we will tell you why we love it.”

On the preprofessionalization of higher ed I would refer readers to Bryan Caplan’s The Case against Education: Why the Education System is a Waste of Time and Money (2018). Caplan argues that overall a degree signals only three things to the marketplace: that the graduate is smarter than average, more conscientious, and more conformist. He believes that higher ed should be eliminated because there are cheaper ways to find these things out about a person. I agree that this is a lot of what higher ed does these days, but I would save it rather than eliminate it.

Norman, your love for the topic of this post oozes off the page!

My contribution to #20: I like to share HOW I learned about my beloved topic. This teaches the students how to pursue deep knowledge of a subject that interests them...how to seek knowledge...how to go beyond what is expected of them. I share my own journey of learning about my subject and in doing so, I demonstrate a model for their own pursuits. Like the saying goes..."Don't tell them, show them."

Norman, this is a fantastic and much-needed piece. Your core argument, that a professor's genuine, demonstrated love for their subject is the most powerful teaching tool deeply resonates. The story of Dr. Gerberding is a perfect illustration; many of us have likely had a similar figure who ignited a passion through their own infectious enthusiasm. Thanks for articulating this so clearly and reminding us what truly matters in education.